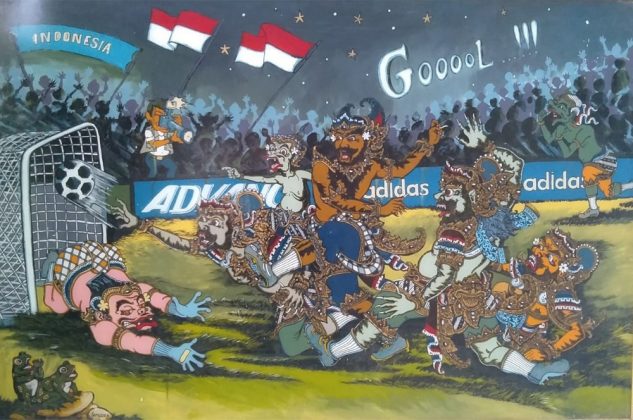

Through The Looking Glass With Lia Sciortino: Indonesian Reverse Glass Paintings, Observerid

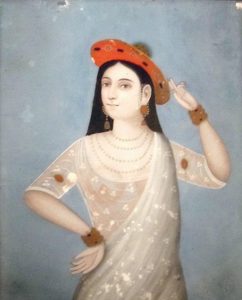

A glass painting of palace and mosque from the collection of Lia Sciortino. (Photo: IO/Tamalia Alisjahbana)

IO – In a reverse glass painting an image is painted on glass but later is viewed from the other side of the glass which often gives the painting more depth. Unfortunately, this makes it also, very difficult to repair or restore should the painting ever be damaged.

Dr Rosalia Sciortino Sumarjono is a cultural anthropologist and development sociologist by training and the founder of SEA Junction, an organization that aims to foster understanding and appreciation of Southeast Asia in all its realities and socio-cultural dimensions from arts and craft to the economy and development. A good-looking Italian woman from Palermo with a strong personality, Lia had already since childhood a love for travel. At the age of 18 she travelled around the world and then stayed for a time in India.

Glass paintings are also often used to depict scenes from independence such as this Solo glass painting which shows the Punakawan raising the Indonesian flag. (Owner of painting: Tamalia Alisjahbana. Photo credits: Yoga/IO)

Her deep interest in other cultures and peoples led her to commence studies in anthropology at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. In 1986 the University was in research collaboration with Universitas Gajah Mada (UGM) of Jogjakarta and Lia came to Indonesia to do fieldwork in Salem (Brebes Regency of Central Java), Muntilan (Magelang Regency of Central Java) and the Central Javanese town of Magelang.

One of the things that Lia discovered was that in the area lived some of the most renown glass painters of Indonesia, painters such as Sastro Gambar for example who she later discovered was the most famous glass painter of the region. She found that many houses there had his paintings on display. And so, from there began what was to prove to be another new and life-long love for Lia namely, Indonesian reverse glass painting.

Another thing that Lia also found in Indonesia was her future husband the renown pencak silat (an Indonesian form of martial arts) master O’ong Sumarjono. She had first met him in the Netherlands where he was giving some martial arts demonstrations but it was in Jogjakarta that she fell in love with him. By then Lia was preparing her PhD thesis and she would go to Jogjakarta in order to telephone home to Italy. O’ong was from Bondowoso and also interested in art and culture and very knowledgeable about glass painting. He was also twice pencak silat World Champion and Southeast Asian Games Champion and starred in a popular television series called Tutur Tinular which had many magical scenes with O’ong flying through the air. He was a martial arts actor and legendary figure to his fans. Later he became an international pencak silat coach as well as researcher and innovator. He was also the author of the influential and fundamental work on the subject, “Pencak Silat in the Indonesian Archipelago”.

A glass painting of a bouraq made in East Java from the collection of Lia Sciortino which she suspects may have been produced in Madura or at least shows signs of Madura influence. Such paintings were used to ward off evil or bad luck. (Photo: IO/Tamalia Alisjahbana)

The result was that for most of her life aside from her own work and research this adventurous Italian lady was also drawn into a world of pencak silat and lukisan kaca or Indonesian reverse glass painting. Lia found that there is a lot of glass painting done in East Java and Madura where aside from being valued for its aesthetics it also has a history of being used to ward off evil and ill fortune from a home. This is especially true of paintings of bouraqs, mosques or Arabic calligraphy. Slowly, through the years Lia and O’ong built up a very large collection of reverse glass paintings.

The art of reverse glass painting appears to have originated in the Byzantine Empire and was used for sacred paintings such as paintings or icons of saints during the Middle Ages. Through the vehicle of trade this style of painting also spread to Italy especially Venice from where it influenced Italy’s Renaissance art. In the 18th century in Central Europe the Church and the nobility became enamored with glass painting and in the 19th century particularly in Austria, Bohemia, Slovakia and Bavaria it became part of the traditional folk art.

A Solo glass painting depicting a scene from everyday life in the village i.e farmers working in the rice fields. (Photo credit: Yoga/IO)

German art historian and Raden Saleh expert, Werner Kraus writes in his paper Chinese Trade Art of Southeast Asia that the tradition of trade spreading the art of reverse glass painting continued into the 18th and 19th centuries bringing the art of glass painting to China where it developed as trade or export art especially in Canton and Macau. Here artists created furniture, painted china ware, oil and water color paintings on paper and canvass for merchants, sailors and sea captains to at first take home as souvenirs and then later when these items proved to be extremely popular, as trade or export items. They also began to produce glass paintings depicting subjects and styles favored by their European buyers. They created paintings of ships and port scenes, pictures of everyday life and portraits and frequently also copies of European prints. However, glass painting occupies a special position within Chinese art for whilst primarily an export art it also had Imperial patronage.

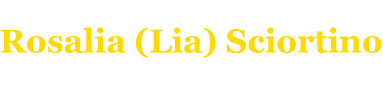

Anonymous reverse painting on glass of a woman, western India, late 19th century, Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art. (Photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/file:anonymous reverse painting on glass of a woman, western india, late 19th century, haa)

By the 18th century glass painting had found its way to India via the China Trade. Indian painters especially in south India began to portray Indian mythology and portraits of kings, nobles, courtesans and musicians. Chinese glass painters appear to have also settled along the coast in Gujarat which also became a centre for reverse glass painting. Meanwhile, Japan imported the art of reverse glass paintings from China during the late Edo period for Japanese artists were drawn to the vibrancy of colours in them and used glass art to depict both Japanese as well as foreign scenes.

Lia Sciortino wonders why the art of glass painting is not everywhere in Southeast Asia. “In Thailand,” she says, “it is only used in temples for astrological signs. In Cambodia glass paintings portray the life of Buddha, in Myanmar it is used to paint nats or spirits and the Buddha but there is no tradition of reverse glass painting in Laos or the Philippines. Why is that?”

More research is clearly needed. Meanwhile, in Indonesia glass paintings are produced in Java, Bali and Madura. Glass paintings from Sumatra are extremely rare. Lia owns two glass paintings from Sumatra but she is not sure if not someone from Java went to Sumatra and painted them. In Java important centres for glass painting are found in Jogjakarta and Solo and along the north coast in West Java, Cirebon is another important producer of glass paintings.

More research is clearly needed. Meanwhile, in Indonesia glass paintings are produced in Java, Bali and Madura. Glass paintings from Sumatra are extremely rare. Lia owns two glass paintings from Sumatra but she is not sure if not someone from Java went to Sumatra and painted them. In Java important centres for glass painting are found in Jogjakarta and Solo and along the north coast in West Java, Cirebon is another important producer of glass paintings.

In this Solo glass painting the Punakawan are depicted as royal soldiers. (Photo: Yoga/IO)

“Central Javanese glass paintings traditionally depict scenery, everyday life, the Punakawan (Javanese clowns) or the loro blonyo (traditional Javanese carvings of a male and female figure in Javanese costume usually sitting cross-legged. They are symbols of fertility as manifestations of Dewi Sri the harvest goddess) or wayangs and now there is often a modern element in the paintings. In East Java the colours are stronger and there are more paintings of Muslim heroes and historical anti-colonial figures such as Diponegoro,” explains Lia.

Cirebon glass paintings are renown for the use of the megamendung or darkening clouds motif which is a symbol of prosperity and also the sunyaragi or cliff motif. Figures in Cirebon paintings are usually wayang. Cirebon is also known for its calligraphic paintings.

Some glass paintings depict important or familiar places as does this Cirebon glass painting of the Keraton Kesepuhan. Note the characteristic megamendung (darkening clouds) motif as well as the sunyaragi cliff motif at the bottom of the front façade. (Photo: IO/Yoga Agusta)

Haryadi Umbara, a well-known Cirebon glass painter says, “It is not known precisely when glass painting first came to Cirebon. Many people think that it originated from China and believe that it emerged under the influence of the Princess Ong Tien who was the fifth wife of the Sunan Gunung Jati (one of the nine guardians who spread Islam in Java. The Sunan Gunung Jati was from Cirebon). In Cirebon the village of Gegesik is known for its traditional glass painters and this is where Rastika, the most famous Cirebon glass painter came from. He has passed away but there are still well-known artists such as Astika Bahendi and Bahenda. I myself, come from the city of Cirebon and was taught by my father Prince Umbara. The name I use is Elang Yadi Wijaya Kusuma.”

Balinese glass painting by Bali’s most famous glass painter Jro Dalang Diah from Desa Nagasepaha; painted in 1928 and entitled “Sitakepondang”. (Photo courtesy of: Hardiman Ahimsa)

Hardiman Ahimsa is an art lecturer and curator from Singaraja, Bali. He has also written Dialek Visual, a discourse on Balinese arts. Hardiman explains that the most important centre for glass paintings in Bali is the village of Nagasepaha in Buleleng. “In the 1920s I Ketut Negara who was also known as Jro Dalang Diah was the most famous dalang (puppet master) and wayang kulit or shadow puppet maker in the village. In 1927 he was approached by a wayang lover named Wayang Nitia who asked him to make a reverse glass painting and so as to help him do so he brought him a Japanese reverse glass painting of a lady in a kimono. Jro Dalang Diah carefully scraped off the paint layer by layer in order to learn the technique of glass painting and he researched the paint he would have to use and then this man who had only a primary school education produced the first reverse glass painting in the village. Before he died, he taught the technique of glass painting to his son and grandsons and neighbours

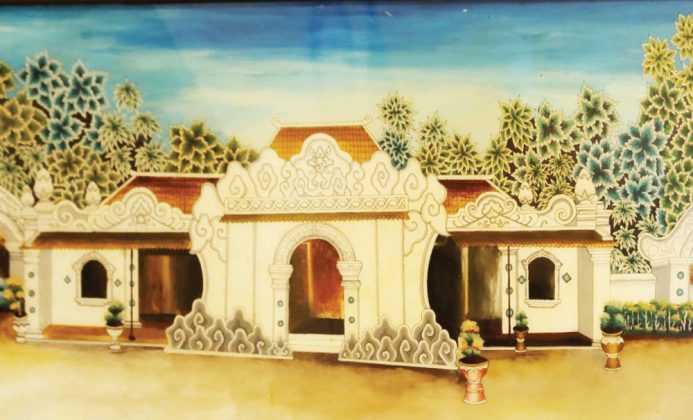

A modern Balinese glass painting by Ketut Santosa, entitled “Sepak Bola” or “Football”. (Photo courtesy of Hardiman Ahimsa)

This is how the village finally became the most important producers of glass painting today.” Jro Dalang Diah created mostly glass paintings of wayang from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Today the most well-known glass painter in Desa Nagasepaha is Ketut Santosa who has exhibited his art in Jogjakarta and at both the Galeri Nasional and the Bentara Budaya in Jakarta. The north Balinese glass paintings display very contrasting colours as opposed to the more harmonious coloring of Javanese glass paintings. The decorative ornamentation is also larger. In Desa Nagasepaha the favourite subjects for glass paintings are still characters from the Ramayana and Mahabharata but also scenes from contemporary social life.

Lia Sciortino speculates that the art of reverse glass painting could have entered Indonesia through three possible routes namely China, India or via the Dutch. She says that glass painting first became popular during the rule of Panembahan Ratu II of Cirebon (1649-1677). He was the sixth ruler of the keraton Pakungwati before Cirebon was split into its various keratons or palaces. Jerome Samuel, director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies in France is of the opinion that glass paintings in Java were first introduced by European and Chinese painters in the mid- 19th century. They are now a blend of Javanese, European, Chinese, and Muslim styles.

Although Lia Sciortino is still very much involved with Indonesia and frequently returns for research, she is now based in Bangkok where she is Associate Professor at Mahidol University and Visiting Professor at Chulalongkorn University. In 2013 Lia Sciortino’s beloved husband O’ong Sumarjono passed away. The following year the O’ong Marjono Pencak Silat Awards was created. It consists of small grants to further research, document and publish knowledge of pencak silat. When he died Indonesia lost its grand master of pencak silat but Lia lost the companion and love of her life. Through it all Lia has kept her love of glass paintings and one possession that comforts her and provides a memory of her beloved husband is a glass painting of them together. (Tamalia Alisjahbana)

Solo glass painting depicts a bridal couple mixed with a dab of nationalism as they are led forward with the flag wrapped around them. (Photo: IO/Yoga Agusta)